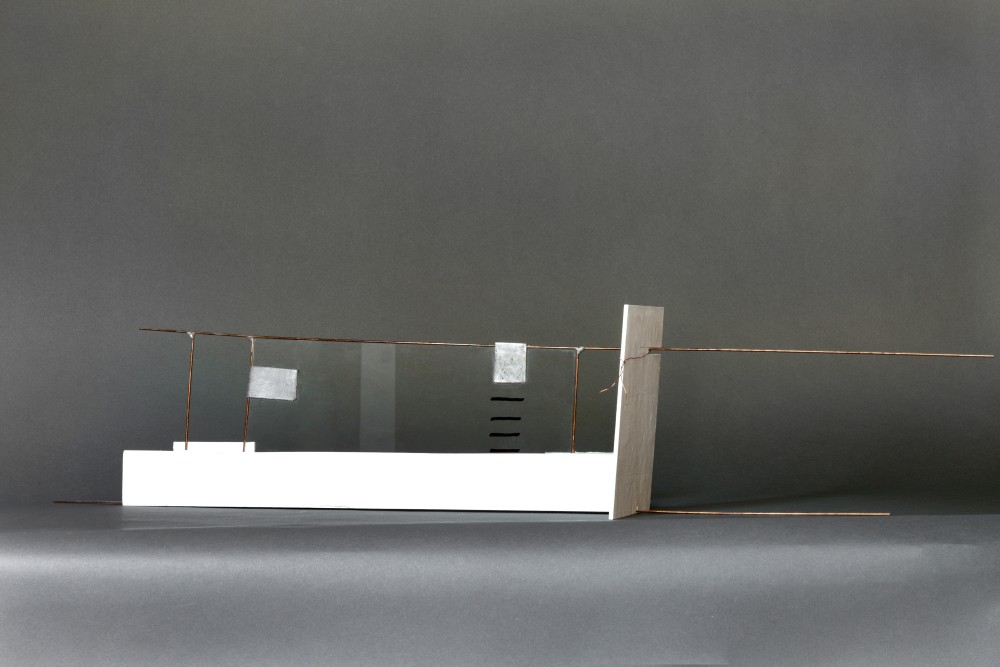

Mark Webber. Untitled. 2019. Copper wire, Hydrocal, Steel, Glass, Permanent Marker. 8 1/8h x 40w x 5d in

THE ONLY LIVING BOY IN NEW YORK

Picasso created his first version of Guitar sometime between October and November of 1912 and in that moment toppled the most fundamental and timeless rule of sculpture: solidness. Guitar consists of 7 pieces of cardboard stitched together with thread, string, twine, and coated wire. This work was likely slapped together in a flash and under the intoxicating sway of a first encounter. Picasso applied the ideas he and Braque had advanced about cubism and collage to an assemblage beautifully visualized in space. The yolk of the egg was broken, and the omelet was born.

Mark Webber assembles many different elements: hand-made, man-made, or found, in striking relationships using steel, stone, wood, glass, and hydrocal. He forges ahead with his visual fragments like a tireless explorer instinctively negotiating and shifting gears in search of surprising places. His images ooze rustic constructivism like a Joaquín Torres-García wood sculpture from 1930 brought up to code. Webber straightforwardly identifies his works in groupings with very simple designations such as structures, walls, portals, and vessels. But a preconscious sparkle also animates his images with anthropomorphic prompts and body language that simulate common gestures like a handshake or a greeting. Encounters between friends.

Some of Webber's sculptures bring together parts or pieces that are curious and tantalizingly difficult. It is not hard to spot a cheeky calculation when a rock is bluntly attached to an L-shaped stucco form with a flat metal bracket that is reminiscent of a deadpan, take-a-hike Buster Keaton routine. In reality, the overall take from Webber's work is elegiac: a solemn wink, a desolate location, and all in the service of commemorating another time and place. While some artists acknowledge the past with subtle pictorial nods, Webber firmly grounds history in the here and now, not unlike Giorgio de Chirico's metaphysical images of empty cityscapes and piazzas. Let's face it: Webber demolishes the present.

The best work of Webber is stoic and evokes an otherworldliness captured, set apart and isolated. His means are cloaked in quiet. Webber graciously spares us the nonsense of nostalgia by fusing fact and fiction, material and message, and a compelling amount of living human quotient. In a cluster, his sculptures create a diaspora of figures vying for attention but clearly performing in unison; collectively they create a timeless model of behavior and comportment. Peter Schjeldahl in his recent article "The Art of Dying" eloquently writes:

I like to say that contemporary art consists of all artworks, five thousand years or five minutes old that physically exist in the present. We look at them with contemporary eyes, the only kinds of eyes that there ever are.

Mark Webber is driven by a belief in the making of sculpture that is endangered. Today art arrives pre-packaged and with a mandatory "identity" meant as "admission" into the club. Gone is the hard-won effort to break free and gain true independence from the slavery of acceptance. Webber defies the odds. His work moves like lava from the mouth of a volcano: slow, deliberate, and mysterious.

- George Negroponte