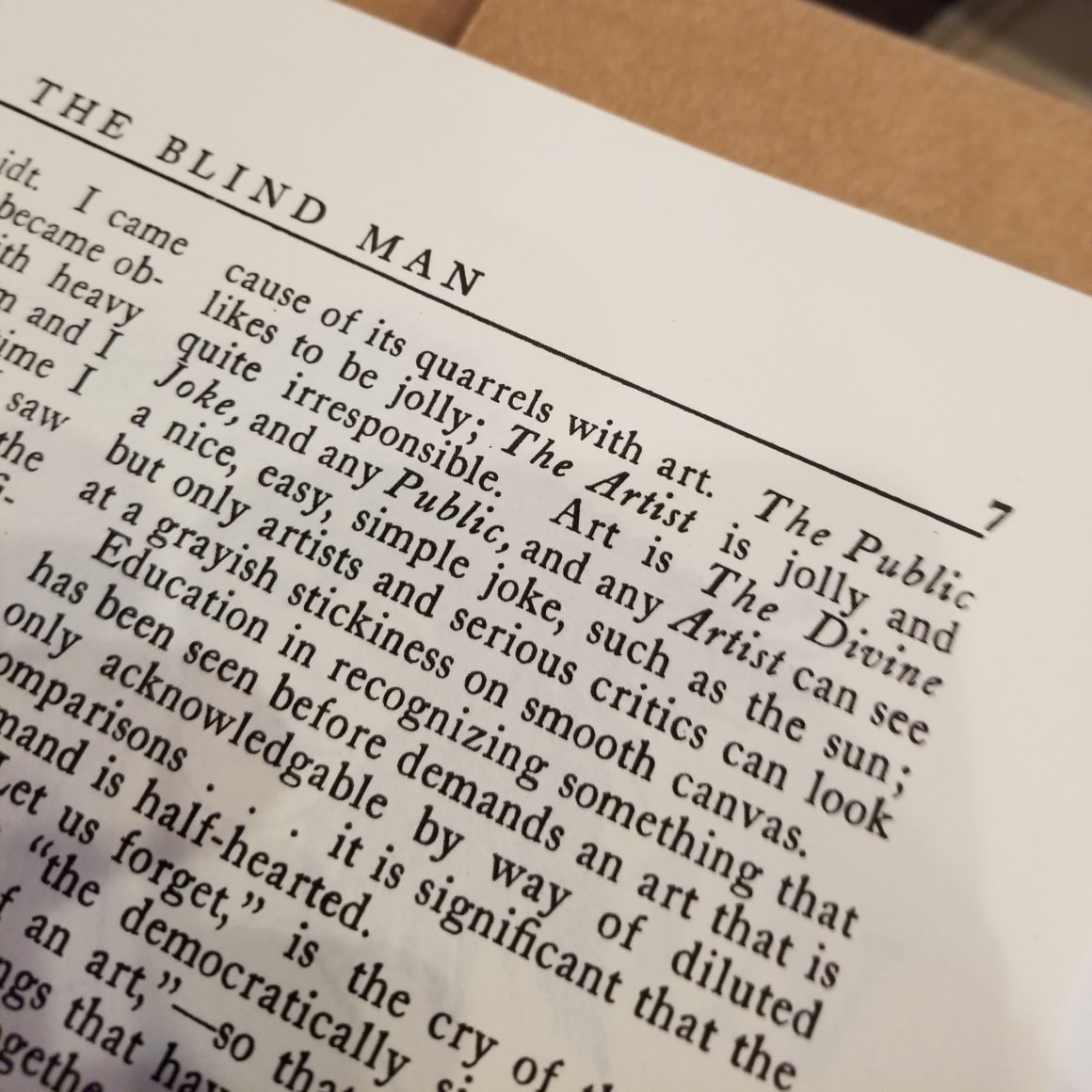

One hundred and one years ago—it seems like only yesterday! Or maybe it’s still tomorrow? April 10, 1917: Henri-Pierre Roché, collaborating with Marcel Duchamp and Beatrice Wood, published the first of what would be two issues of The Blind Man. A fourth contributor was the poet Mina Loy, who contributed the little magazine’s closing piece, titled “In . . . Formation.” There she wrote: “The Artist is jolly and quite irresponsible. Art is The Divine Joke, and any Public, and any Artist can see a nice, easy, simple joke, such as the sun; but only artists and serious critics can look at a grayish stickiness on smooth canvas.”

Reading this, I began to wonder: Would it be possible to go against the spirit of our time as Loy and her friends went against the spirit of theirs, and in so doing reclaim for art something of this solar humor, this celestial irresponsibility?—to present such a notion without entirely losing one’s status as a serious critic.

I thought I’d better try.

The idea would be to present some paintings, or works in the vicinity of painting (some of them are really photographs), that seem to me to embody the divine joke that Loy cracked a century ago. Some would be by artists whose work I’ve followed for some time, but others would come from practitioners I’ve only recently discovered—for spontaneity is essential to humor, isn’t it? In the end I chose a geographically and generationally dispersed six:

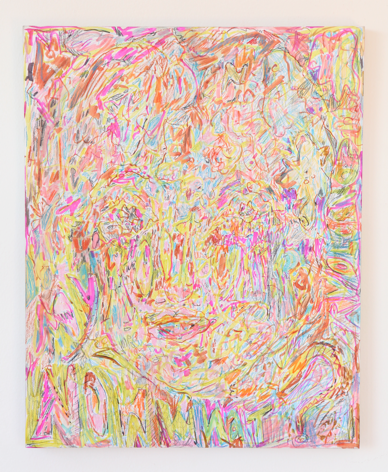

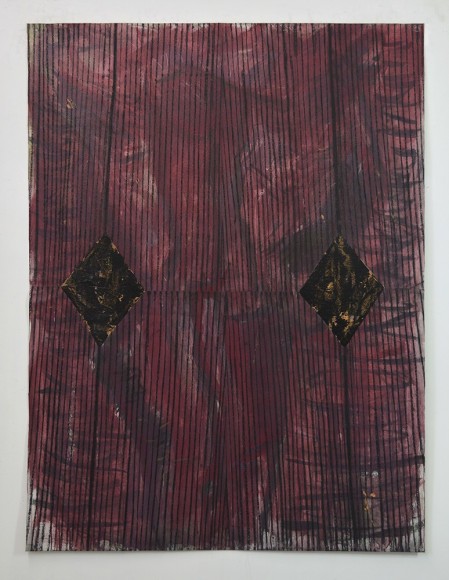

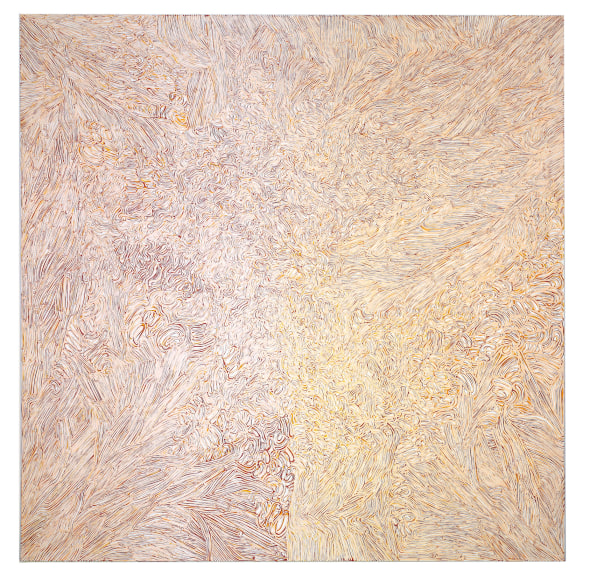

Hayley Barker lives in Los Angeles. Her visionary paintings are relentless storms of mark-making that always have a face; it might evade your glance or stare you down. Varda Caivano—born in Buenos Aires but a longtime Londoner—makes some of the most elusive paintings being done anywhere today; they turn their maker’s dissatisfaction with almost any solution into a kind of involuntary ecstasy. Embracing the ambiguity between figuration and abstraction, Brooklyn-based Sarah Faux creates visual metaphors for jouissance and they practice what they preach. Los Angeleno Adam Moskowitz also cultivates the edge where images go abstract, but his photographs printed on concrete bliss out on space and structure rather than dwelling in the organic. The ever-mutating fields of Francesco Polenghi’s paintings recall the sea, whose constantly fluctuating surface reflects its immovable depths: constant transformation as the appearance of a stable and unchanging underlying process is the subject of this Milanese artist’s work. Finally, Puerto Rican-born, Brooklyn-based Rafael Vega has spoken of wanting painting to “force its immediate past into a state of ‘vibration’ (try to imagine a delocalized electron), by small tweaks”; his recent unstretched canvases let that vibration get stronger than ever. All six of them fulfill Loy’s definition of The Artist—and yes, she always capitalized the word and put it in bold—as someone who can “never see the same thing twice.”

—Barry Schwabsky